Bee-flies are probably the most familiar of all the species covered by the recording scheme. One species in particular, the Dark-edged Bee-fly Bombylius major, is a familar sign of spring as it hovers over flowers and uses its long proboscis ('tongue') to feed from them.

But there are a number of other bee-fly species to look out for as well, and this page collects together some information about the group.

Join in with Bee-fly Watch

If you've seen a bee-fly please let us know! To find out how go to our Bee-fly Watch page.

Why record bee-flies?

To be honest, the main reason for setting up the Bee-fly Watch project was simply to encourage people to enjoy watching bee-flies! And of course you don't have to send in a record to have that enjoyment. But if you are willing to take the extra step to add your photo and record details it makes a valuable contribution to the monitoring of these species. The data is shared and gets used for research and conservation purposes. Dark-edged Bee-fly is widespread and frequent, so is not of conservation concern, but the information we get from Bee-fly Watch allows us to assess changes in the flight period (phenology) and we can also gather information about their behaviour, e.g. which flowers they visit most often.

And not so long ago the Dotted Bee-fly was considered to be a declining and possibly threatened species. In more recent years that has turned around, and the Dotted Bee-fly is expanding its range (probably a result of climate change), although it is still much more restricted than the Dark-edged Bee-fly. That is good to know, but the only reason we do know it is because people send in their records each year. So please continue to enjoy watching bee-flies, and if you can send in your records as well that is a win-win!

Bee-fly life-cycle

For such cute, fluffy insects, bee-flies have a rather gruesome way of life! Bee-flies in the genus Bombylius lay their eggs into the nests of solitary mining bees. To do this (in at least some of the species) the adult females collect dust or sand at the tip of their abdomen, using it to coat their eggs, which helps protect the eggs from drying out. The female next proceeds to find areas of ground where solitary bees have made nest-burrows, hovering over the burrows to flick her egss into them (see video below).

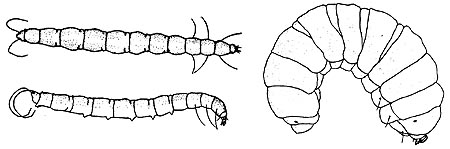

The bee-fly's larva hatches, crawls further into the bee burrows and waits for the bee's own larva to grow to almost full-size, at which point the bee-fly larva attacks the bee larva, feeding on its body fluids and eventually killing it. This is bad news for the bee of course, but bee-flies and bees have lived side-by-side for many millennia, and there is no evidence that bee-flies cause any major decline in bees.

For more detail on the bee-fly life-cycle see Louise Kulzer's account on the American "Scarabs" Bug Society, from which the above image of Bombylius larvae has been borrowed.

Bee-fly links

- Erica McAlister of the Natural History Museum has a great Meet the bee-fly article.

- See also Erica's bee-fly contribution to the UK Wildlife podcast, plus the Natural History Museum bee-fly factsheet (pdf download).

- Dave Hubble's account of finding bee-flies and bees on a small grassy bank in Hampshire.

Bee-flies on YouTube

- Roy Kleukers' video of Dark-edged Bee-fly in the Netherlands, flicking its eggs into nesting burrows of the solitary bee Andrena vaga:

- Dark-edged Bee-fly visiting Bugle flowers (Martin Harvey):

- Dark-edged Bee-fly visiting flowers (Ton Vranken):

- Dark-edged Bee-fly flicking the tip of its proboscis! The proboscis is surprisingly mobile and is under the fly's control, enabling it to feed on both nectar and pollen from a varierty of flowers (for more information on the proboscis structure see Szucsich and Krenn 2002; video below by Martin Harvey):

- Dotted Bee-fly in flight in Spain (Vivencia Dehesa reserve):